Representation of

DISABILITY

Disability in the Media

Film and TV

Image: Hands holding a clapper board

Overview

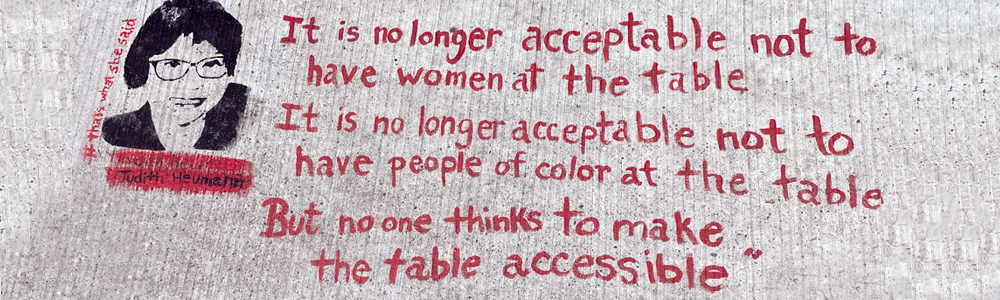

“It is no longer acceptable to not have women at the table. It is no longer acceptable to not have people of color at the table. But no one thinks to see if the table is accessible.”

— Judith E. Heumann

(From Roadmap for Inclusion: Changing the Face of Disability in Media)

In 2019, the Ford Foundation published a white paper, Roadmap for Inclusion: Changing the Face of Disability in Media opens in new window regarding the lack of authentic representation of disability in the media. According to the guide, representation of disability in the media should be: one in four people; in front of and behind the camera; in characters, actors, producers, directors, in writers’ rooms and more (Roadmap for Inclusion, 2019).

Developing an Understanding

There is a lack of representation of disabled people in film and television, and when disability is present, it is often portrayed with formulaic tropes that perpetuate and deepen ableist stereotypes and cliches of disability including:

- The angry, bitter wheelchair user, who can’t get over their lost abilities and lashes out at all non-disabled people (Forbes, 2020).

- The mystical blind person who has ‘extra’ or enhanced senses and ‘sees’ more than sighted people (Forbes, 2020).

- The child-like and virtuous intellectually disabled character who is innocent and good to everyone they meet (Forbes, 2020).

- Disabled people portrayed as either selfish and demanding to be catered to without considering other people or as self-denying, insisting that friends, family, and lovers ‘go on and live their own lives’, leaving them behind (Forbes, 2020).

- Disabled people who are ‘better off dead’. This is one of the most harmful and most popular disability themes, in which a disabled person fights for the right to die by suicide. And the film encourages the audience to see this as a rational or selfless wish (Forbes, 2020).

The Ford Foundation report suggests that the problematic depiction of disabled people in media, film, and television tend to fall into one of four stereotypes.

The Super Crip

Super Crips are disabled characters who triumph over their disability. The Super Crip stereotype reinforces that disability is something that must be overcome. Super Crips often appear in ‘inspiration porn’ as they are portrayed as being inspirational for overcoming their disability.

Examples:

- Daredevil in the Daredevil TV series (2015)

- Professor X in the X-Men film series (1999 – present)

The Villain

The villain stereotype plays on people’s inherent discomfort with people who do not look like them. Disfigurement and disability in general make characters revolting and morally wrong, reinforcing the notion that we should be afraid of people whose faces and bodies are different from ours.

Examples:

- The Joker in The Dark Knight (2008)

- Voldemort in the Harry Potter movies (2001 – 2011)

The Victim

Disabled characters are often portrayed as one-dimensional characters victims of their disability. Film and TV series portray disabled life as one not worth living and present suicide as a better option.

Examples:

- Will Traynor in Me Before You (2016)

- Maggie Fitzgerald in Million Dollar Baby (2000)

The Innocent Fool

Characters labelled with intellectual disabilities are often portrayed as always happy, childlike, and unable to make their own decisions. They are seen as people to be bullied and laughed at.

Examples:

- Raymond in Rain Man (1997)

- Forrest Gump in Forrest Gump (1993)

— Adapted from Roadmap for Inclusion: Changing the Face of Disability in Media opens in new window

Statistically:

- Only 3.1 percent of primetime broadcast TV series regulars—or a total of 27 characters—have disabilities (GLAAD, 2020).

- Across the 100 top-grossing movies of 2016, only 2.7 percent of characters were depicted with a disability (Octane Seating, 2021).

- In 2018, 12 percent of disabled characters on television were played by disabled actors (Ruderman Foundation, 2018).

- In 2018, only 1.6 percent of speaking roles in films were disabled characters (Disability Scoop, 2019).

- Nearly half of the films across the top 100 did not include a single character with a disability (Roadmap for Inclusion, 2019).

- In the history of the Academy Awards, 61 actors have been nominated for Oscars for roles where they played a disabled person. 27 actors won an Oscar but only two were disabled actors (Octane Seating, 2021).

- 95% of disabled characters in film are played by able-bodied actors (Octane Seating, 2021).

Deepening your Understanding

There is a long history of able-bodied actors playing disabled characters in film and television and winning acclaim and awards. Think of Tom Hanks in Forrest Gump, Eddie Redmayne playing Stephen Hawking in The Theory of Everything, Brian Cranston in The Upside, Ben Stiller in Tropic Thunder, and many more.

Here are some thoughts from disabled actors and activists about representation of disability in film and television.

Actor and comedian Maysoon Zayid notes that disabled people make up about 20% of the American population yet the number of disabled characters on film and television is much smaller (3.1% according to a report by GLAAD in 2020). “The message being sent out to disabled kids is you do not belong in this world,” Zayid says. “It would be really helpful to have a disabled Disney princess” (AP News, 2020).

Esme Mazzeo says “Growing up … I didn’t have grand visions of being a movie star or a doctor or a big shot on Wall Street with all of the glamorous trappings that sometimes come with those professions. Perhaps this is because I rarely saw anyone who looked like me on my screen. Watching disabled people on screen achieving their goals might have helped me build more intricate dreams of my own. When I say, “disabled people,” I mean characters played by actors who live with a disability. As soon as I learn that a non-disabled actor is playing a disabled part, it reinforces for me that the world literally doesn’t think people with disabilities can play ourselves.” (Rooted in Rights, 2020).

Disability activist Vilissa Thompson makes this point as well: for disabled characters in film and television to be authentically portrayed, disabled people must be the writers, showrunners, producers, actors, and directors hired to tell the stories. Allowing disabled characters to go from one-dimensional, problematic depictions to being humanized and realistic is due to not being given the space to be a part of the creative development. “Nothing about us without us” proclaims that disabled people are at the forefront in the way disability is understood and represented in the media (Center for Disability Rights, 2017).

“Disabled people come in all shapes and sizes, from wheelchair riders to people with psychosocial disabilities to those with chronic illnesses. From the Hispanic deaf person to the legally blind African American who has albinism to the Asian lesbian wheelchair rider, diversity is intersectional, and the media must reflect this. Not only do disabled people need to see themselves, but their families and communities need to see disability on their screens. Most people acquire their disabilities as they become older, so people should be given the opportunity to learn about the diversity in this community.” (Roadmap for Inclusion, 2019).

Spotlight: The Centre for Independent Living in Toronto (CILT)

The Centre for Independent Living in Toronto (CILT) staff are frequently called on by media to comment to the media on subjects involving accessibility. One recent project has allowed people with disabilities to become the storytellers. The D-Next Accessible Media Lab is led and run by a creative team of new media artists, film makers, journalists and advisory members with disabilities and trains and supports emerging media storytellers who tell community stories through a variety of platforms including podcasts, mini documentaries, blogs, and more. D-Next connects with people with disabilities from underrepresented populations in Toronto to tell and circulate their stories. CILT views D-Next as a valuable resource for producing authentic portrayals of people with disabilities who are under-represented in mainstream and social media, told through a “nothing for us without us’ lens (CILT, n.d.).

In 2019, six disability activists and experts met to discuss representation of people with disabilities in the media and popular culture in Canada. Participants discussed the current landscape of media representation and some ways it can be transformed to be more inclusive and accepting of people with disabilities to accurately represent their lives and stories.

Disability Representation in the Media and Popular Culture in Canada opens in new window was produced by the Centre for Independent Living in Toronto (CILT) and D-next Accessible Media Lab (CILT, n.d.).

Disability Representation in the Media and Popular Culture