TELLING STORIES

Introduction

Book publishing is, at its most basic level, a collective act of disseminating stories. Each of the millions of books that are published around the world every year, in a large and ever-growing range of formats and genres, is an attempt to share a story.

Why do we tell stories? To connect, certainly, to entertain, inform, warn, charm, captivate… the possibilities are endless. Storytelling is part of the way we process, react to, and understand the world around us, which is reflected back to an audience who can then grow their own understandings.

But only if everyone is included.

Accessibility in Publishing

Book publishing cannot be seen as a set of traditional practices - creative, cultural, mechanical, and economic - but as a constantly evolving conversation that seeks to draw in more and more listeners and participants. The need for greater accessibility has often been understood as an ethical or legal issue, where a demand is made by a group and then imposed on an organization by an outside authority, often a government. In other words, we made things more accessible because we were told we had to. This reductive view of accessibility is, we hope, becoming more and more rare as more people and more institutions recognize the need for accessibility to be a primary consideration, not an afterthought.

In book publishing, this means a move away from thinking of the traditional book - printed in ink on paper, bound within covers - as the central product, with all variations on it being merely extras or a bonus. The rise in popularity of e-books, audiobooks, and other variations of texts in digital form is helping to spur this shift, but the reality is that printed books have only ever been one among a myriad of storytelling devices, both physical and conceptual.

This section explores the fundamental principles of print disabilities, as well some of the many approaches to communication and storytelling that pre-date the advent of the printed book. It also provides a brief history of the book as an object, and points toward an understanding of texts and literacy that is expansive and inclusive. "'The book' is a more flexible and abstract conceptual category than many people imagine, and it is this very quality that makes it interesting," writes Leslie Howsam in The Cambridge Companion to the History of the Book. "There were books before printing, and the manuscript practices that reproduced texts before the use of printing still flourish generations after Gutenberg." Or, as New Zealand literary scholar D.F. McKenzie has put it: "What we too readily call 'the book' is a friskier and therefore more elusive animal than the words 'physical object' will allow." (The Cambridge Companion to the History of the Book, 2014).

Disability Oral History

Image source: Etienne Giradet/Unsplash

For centuries, history was written by collecting the accounts of bystanders and participants who witnessed, participated, or lived events. Oral histories were first collected for research analysis in 1948 at Columbia University by narrative historian and journalist Alan Nevins, who realized that memory was an important source for information. As a journalist, he met many people whose stories would die with them unless they were recorded. He knew that important historical research tools such as letters and confidential memos, were being replaced in the modern world by telephone conversations that were not recorded. Nevins established the Columbia Center for Oral History in 1948, now home to over 10,000 transcribed oral interviews.

The history of disabled people is complex and not well known. It is often written by people without the lived experience of disability, and therefore often doesn't include the perspectives and voices of disabled people. Recording disabled people's oral histories creates inclusive space for the latter to speak for themselves and adds to disability culture by acknowledging their lived experience. Everyone with a disability has a unique experience; they are experts in their own lives.

The Disability Oral History Toolkit was compiled with the support of Centre for Independent Living in Toronto (CILT) and the Department of Physical Therapy at the University of Toronto. This guide is a key source for developing oral history projects based on the lived experiences of disabled people. Focused on access, collaboration, and foregrounding a critical disability perspective, it offers ways to center narratives that are often ignored in favour of medical definitions and narrow-minded, stereotypes and descriptions.

Understanding Print Disabilities

According to the Centre for Equitable Library Access (CELA), a print disability prevents a person from reading conventional print. More specifically, a print disability can be a:

- Learning disability: An impairment relating to comprehension and understanding

- Disability: The inability to hold or manipulate a book or turn its pages

- Visual disability: Severe or total impairment of sight or the inability to focus or move one's eyes

Print disabilities may include visual disabilities as well as cognitive disabilities, memory loss, dementia, learning disabilities, comprehension and processing disabilities, dyslexia, neurodiversity, and physical disabilities including limb differences.

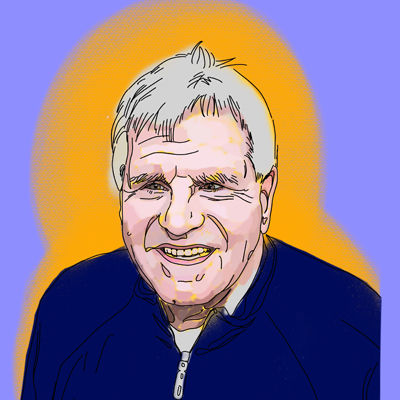

Profile: George Kerscher

Illustrations by Rachel Asevicius

George Kerscher is an American multi-award-winning expert in technological accessibility solutions. Kerscher coined the term "print disabled" in the 1980s and developed the concept of "computerized books" for people with print disabilities. Kerscher was elected as project manager for the DAISY (Digital Audio-based Information System) Consortium in 1997, and helped the organization become an international leader in designing information systems for print-disabled people, including designing EPUB accessibility standards and tools.

In his 2018, Kerscher received the Dr. Isabelle Grant Award for individual initiatives which benefit people who are blind. In his acceptance speech, he pointed to the need for increased accessibility in the STEAM fields as accessibility advances: "Knowledge that is communicated through symbols, such as that used in the fields of Mathematics, Chemistry, and Music, is just beginning to become accessible, and the standards and technology must improve in these domains. We have made great strides together and we need to continue the march toward full access to information and knowledge."

What is a Print Disability?

It can be easy to understand why people with visual impairments or learning disabilities might experience something called a "print disability." However, there are many other conditions and social situations that constitute barriers to print content that are less obvious or easily recognized.

Sheyfali Saujani, who is partially blind, understands that services targeted at people with visual impairments do not always address the needs of those facing other barriers to print. What is a Print Disability? reveals unexpected ways in which a print disability is experienced by diverse people with different backgrounds; people whose needs are often overlooked by content producers.

Sheyfali reflects on the process of making this film with her team, Diana Bahirian and Yhasmina Garcia:

We shot this film over several months in early 2022, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although we were able to film some people in person, other interviews were conducted over Zoom. Zoom and other similar technologies became widely used during the pandemic and enabled people with mobility impairments to participate in remote meetings in ways that were previously not considered possible during Covid lockdowns. In that sense, I suggest that the pandemic was a "world disabling event," in which lockdown restrictions "disabled" large sectors of society.

This is one example of the social model of disability where attention to barriers rather than bodily impairments or diversity is recognized as the critical cause of disability. When non-disabled people were confined to their homes, many accessibility options that disabled people have been asking for, were, as we see in the film, made available. We hope this film reminds content producers of how the disabling impact of the pandemic led to creative solutions that can be replicated in other contexts.