Producing Accessible

Audio & Video

Accessible Video: Captions

Understanding Captions

Developing an Understanding

Film, television, and online video form content for a large part of the Canadian media experience. Discussing what we’ve recently binge-watched or sharing opinions on social media is a significant part of the media experience. Recaps, reactions, and deep dives on relevant cultural content offer ways to connect with fellow fans.

Captions make video available to more viewers, which also broadens the audience for content creators and media makers across platforms, including TikToks, Instagram reels, and daily vlogs. If people who are d/Deaf or hard of hearing are left out of the conversation because of a lack of captioning, it makes the content itself inequitable.

The terms “captions” and “subtitles” are often used interchangeably. At first glance, they may seem to be the same thing – they both appear as text on screen. In Canada, captions are not the same things as subtitles. When subtitles are being used in a video, their purpose is to translate the language of the video into whichever language the intended audience is fluent in (most Canadian programming offers English and French). For instance, in Canada, a Russian film might have subtitles in English or French so that an audience who does not speak Russian can understand the story. Subtitles only show the words that are said onscreen whereas captions translate all of the sounds in a video into onscreen text including background noise, into text (The Closed Captioning Project, n.d.)

Creating Captions

SubRip (SRT)

SubRip files (SRT) are plain-text files that contain caption information. They include start and stop times and the caption text, ensuring they’ll be displayed at exactly the right moment in the video. SRT files work on most media sites that let you upload captions.

To create SRT files:

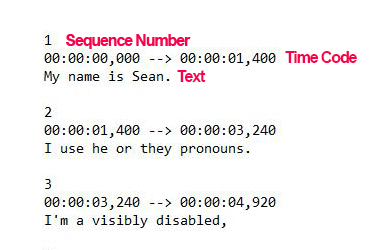

SRT files begin with the sequence number; the beginning and ending timecode for that section stating hours, minutes, seconds, and milliseconds; followed by the actual text. Keep in mind that every break and punctuation mark is important.

SRT files begin with the sequence number, the beginning and ending timecode for that section stating hours, minutes, seconds, and milliseconds, followed by the actual text.

Keep in mind that every break and punctuation mark is important.

The time code is written as:

00:00:01,400 -- > 00:00:03,240

Hours: 00 followed by a colon (:)

Minutes: 00 followed by a colon (:)

Seconds: 01 followed by a comma (,)

Space, two dashes (--), right arrow (>)

This video by REV opens in new window, explains how to create an SRT file.

Automatic Captions

Automatic captions are generated using speech recognition technology powered by machine learning algorithms or Artificial Intelligence (AI), which is software that is able to recognize patterns. Automatic captions might misrepresent the spoken contents due to accents, dialects, mispronunciations, background noise, and use of jargon and often fail to use correct punctuation or capitalization. While the accuracy and efficiency of AI technology is always improving, it does not offer 100% accuracy and requires significant editing. But they can be used as a starting point for developing accurate captions and transcripts.

Accurate captioning of at least 99% accuracy is the only way to ensure that people who are D/deaf or hard of hearing can understand audio content. Automatic captions should never be used as a substitute for captions or sign language interpreting.

Deepening your Understanding

In 2016, Humber Polytechnic Professor Anne Zbitnew led a research project with faculty and students from the Media Foundation program in the Faculty of Media, Creative Art, and Design (FMCAD). The project was called Beyond Compliance: A Student-Centered Study on Accessible and Inclusive Video Captioning. The research question asked was: How does learning how to caption video affect students’ perception of the importance of inclusive design in video content? Student participants attended two workshops where they learned about captioning history, transcription, and captioning grammar. They experimented with various techniques and applications of video captioning. Each participant completed an entrance survey, an exit survey, and a video exit interview. Their responses helped develop tools for further inquiry into inclusive design and accessibility in the FMCAD Media Foundation program at Humber Polytechnic. As a result of this project, all Media Foundation video projects are required to be transcribed and captioned. Former Humber Polytechnic Film students Alex Vaillancourt and Julien Zakrzewski documented the workshops, recorded interviews, and captured and edited the following video.

Here are some selected student interview responses to questions about captioning video:

You can actually learn new vocabulary.

You can actually understand what they're saying easier, and it's an overall better learning experience and viewing experience of whatever you’re watching, TV, film, whatever.

I don't read a lot of books, but I read a lot of subtitles. It's like reading a script for me, so I find that very helpful because I want to do filmmaking and script writing and all that. It's just helpful to know the flow and everything.

Because I oftentimes miss words, I miss things that are said. It also helps with comprehension. If there's a word I don't know, if I see it, chances are, I'll understand it better. I like to read as I watch. It helps with memorizing words.

I use captioning when watching movies. With background noise, you do miss a large part of the dialogue. I do not like listening to TV or music very loud.

Closed captioning is literally the best resource for anyone with ADHD because your mind races a mile a minute and sometimes you can't catch up with what they are saying on TV but your eyes can read that fast or vice versa. I am pro-closed captioning!